GaitKeep: Multi-Modal Approach to Gait Authentication

A break-down of an (incomplete), machine-learning based authentication system 28 Mar 2020Introduction to GaitKeep

This post is about “GaitKeep”, a group project that our team completed for a mobile computing class. GaitKeep was a multi-modal approach to biometric authentication that verified users through a combination of accelerometers (from a mobile device) and video-camera to increase security and consistency of gait authentication. Instead of using older machine learning technique to classification (like PCA), GaitKeep used deep-learning models to perform classification. GaitKeep was only 75-85% finished, but I thought it’s still important to document our work and decisions we made.

1) Background

2) Design & Engineering

3) Classification System

4) Conclusion & Results

Background

What is Gait Authentication?

Gait authentication is the process of verifying identity through their walking patterns with sensors like pressure-sensing plates, accelerometers, gyroscopes, or a camera. This could be framed as gait identification (classifying an individual based on their walk) - where the goal is to maximize accuracy. Authentication wants to confirm a proposed identity - figuring out that Alice is actually Alice by analyzing her gait. Identification is involves identifying a given (anonymous) gait pattern and labeling it as Alice.

Why Gait Authentication?

Your gait is a “biometric” measure - meaning that it is a characteristic that we can observe or compute from your patterns. Biometrics are ideal for authentication because instead of relying on a password (something you remember) or an ID card (something you have), it relies on your identity. By making authentication about your identity, rather than something you need to memorize or own, you can prevent attackers who have obtained your passwords or ID cards.

Biometrics are becoming increasingly popular because they offer improvements where traditional authentication (passwords, pins, etc) fails. In addition, there is a usability aspect to biometrics as well - where tapping your fingerprint or scanning your face is more “seamless” than trying to remember a password or trying to scan a card.

Common Exploits for Common Authentication

The reasons why we care about Biometric authentication is that it can be more secure than traditional authentication systems (I emphasize “can” because bad biometric authentication can exist). Aside from not being careful with usernames and passwords, there are plenty of well known attacks for breaking into accounts that involve social engineering or subtle flaws in a service.

For example, say that account information was leaked because of a data breach at dropbox. If you use the same email & password combo for your dropbox, social media, banking, and online shopping accounts, your accounts might be in trouble. People who have a copy of the leaked files can try all the possible email and password combos on these other services! As a result, even though you changed your dropbox password - all your other user accounts have been compromised (and you need to change all the password to all your other accounts). This is why when leaks like this occur, you need to change your password on all your other accounts, and it’s advisable to have multiple passwords (but who really wants to memorize all those passwords)?

If you’re not sure your credentials have been leaked, you can check services like “have I been pwned?” that checks if your email address & password has been leaked

This is just one of the easy ways that people can exploit username/password authentication systems, but there are more and more ways. People can attack your accounts through your SIM, keyloggers, and clever password cracking. Sometimes the companies holding your information might make the mistake. Twitter was compromised through a social engineering attack and CapitalOne was breached by a misconfigured setting giving access to employees (there are just a few and recent examples, there are a lot more if you look).

Why Multi-modal Authentication (why use more than one sensor)?

One of the influences on our project design was the success of multiple sensors in RAPID (Rapid: A Multimodal and Device-free Approach Using Noise Estimation for Robust Person Identification). RAPID was motivated by the success of device-free sensing that focus on using WiFi to identify individuals (Some examples are “Gait recognition using wifi signals”, “WiWho”, “WiFi-ID”). However, these systems were incredibly sensitive to noise, and the authors of the paper believed that they could improve identification performance by using an additional acoustic sensor (microphone). The acoustic sensor estimated system and environment noise (a “noise estimation” process) to see the noises influence on the wifi-signals. Afterwards, they processed the signals and performed the traditional gait analysis used in other models. As a result our group thought that there was potential to augment computer-vision based gait classification with accelerometer data to create more accurate classifications.

Besides accuracy, we thought that using a multi-modal approach to authentication would provide higher security through more stringent requirements. Despite its strengths, biometric security can still have weaknesses and potential attacks. For example, the fingerprint sensor on the galaxy S10 was tricked by a 3D printed finger. You could argue that this attack is very unrealistic or that important security facilities would have a more sophisticated sensor (and I agree about these), but these exists viable attacks. By requiring additional biometric data to be collected, we can (attempt to) increase the security of our system.

Biometric Authentication - a quick review

Biometric authentication systems verifies its users through a unique physiological or behavioral characteristics (some popular examples include fingerprint login, face-id, etc). Naturally, you might notice that there are some important factors that determine the viability of a biometric signature.

Factors determining the usefulness of a biometric system include:

- Universality - does everyone have this trait?

- Uniqueness - is this trait unique to every individual?

- Permanence - does this trait stay the same, or does it change over time?

- Measurability/Collectability - is this trait feasible to measure or compute?

- Performance - how fast and accurate are systems using this trait?

- Acceptability - will people accept this biometric trait being used?

- Circumvention - how easy is it to imitate this trait?

For example, fingerprints are:

- Universal (almost everyone has one)

- Unique (everyone’s fingerprint is unique)

- Permanent (you fingerprint shouldn’t change over time)

- Measurable (we can accurately track and measure a fingerprint with a special sensor)

- Fast (seems to work fine - not an expert on the engineering)

- Acceptability (most people are okay with having their fingerprint taken)

- Hard to imitate (No matter what spy movie or show tells you, it is hard to duplicate a fingerprint)

If we think about gait patterns, they also fulfill the requirements! Although, the speed, measurability, and acceptability of gait authentication depends on the implementation.

Design & Engineering

The Goal

Our goal was to improve gait authentication (increase accuracy and security) by using a combination of sensors rather than just relying on one.

Unfortunately, attempting to design a system can get complicated very quickly - and the scope of possible implementations and fine-tuning options make finding “the best” configuration hard. We choose accelerometers in the phone and a web camera. Gyroscopes were excluded because of debugging issues we couldn’t solve in time (but we would have liked to include them).

Security, Usability, & Confusion Matrices: False Positives, False Negatives, and Other Metrics

We want our authentication system to be as accurate as possible! It should work all the time and be perfectly secure! However, it’s important to understand that if perfect accuracy is unachievable, we should decompose how our authentication scheme fails and prioritize security or usability.

This is where I think a “confusion matrix” provide an easy way of conceptualizing concepts as well as gifting us well defined terminology and evaluation metrics. As a user, the type 1 and type 2 errors (“False Positives” and “False Negatives”) greatly affect usability and security. The authentication’s usability is affected by the its false negative rate (i.e when it should be authenticating us but isn’t) while its vulnerability is proportional to its false positive rate (i.e when it’s authenticating things it shouldn’t).

Silly Examples

Suppose a system has a 0% false positive rate (FPR) and a 25% false negative rate (FNR). Our system would be incredibly secure - there is absolutely no potential for someone to accidentally be identified as you (0% FPR). However, using this would be incredibly annoying. 1 out of every 4 times (25% FNR), the system fails to correctly identify us, and we need to attempt another pass through.

On the other hand, suppose a system has a 20% FPR and a 0% FNR. This system is very usable, its almost seamless! The system will always be able to identify that it is you (0% FNR). The tradeoff is that a random person could authenticate with your credentials 1 out of 5 times.

I listed these (impractical) examples because having a 99.9% accuracy is very good, but still results in failure 1 out of 1000 cases. Even though it’s not very practical to try a biometric attack 1000 times, thinking about type 1 and type 2 errors let you prioritize whether you want to sacrifice usability or security in that 0.1%.

Our Approach: Combining accelerometers and video

Our two multi -modal approaches data approaches were to use the accelerometers on the mobile device assisted with the camera feed of the individual walking. We also wanted to use the device’s gyroscope as well (because other gait recognition systems on mobile devices used it as well), but consistency issues and time constraints prevented us from completing it.

Furthermore, we use convolutional neural networks (CNN) on the sensor & video feed to perform classification. While it is intuitive to apply CNN’s for classifying gaits visually, it might not be intuitive to apply it domains outside of image processing. However, different research groups have tested the effectiveness of CNN’s in signal processing and have found moderate success. For example, “Deep Learning-Based Gait Recognition Using Smartphones in the Wild” has used CNN’s in conjunction with an LSTM to recognize user’s through their smartphone.

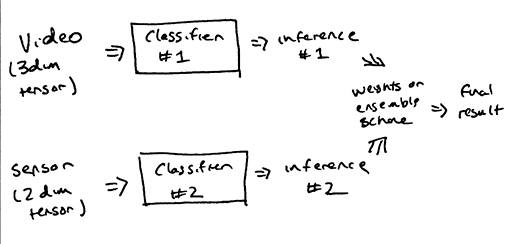

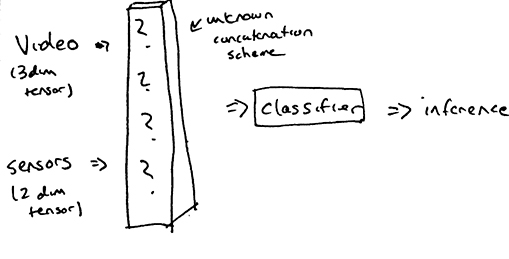

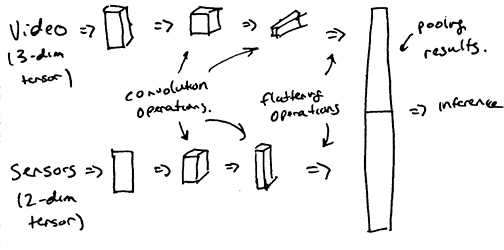

Potential Authentication Schemes

There’s a few ways our classification scheme can approach authenticating users. We can tyrgm different models trained on their respective sensors, relying on their consensus to authenticate users (i.e ensemble classification). We can concatenate the data from both accelerometers and camera to form a single feature tensor (i.e feature concatenation). Or we can process our two sensor sources with different CNN’s and merge their flattened neurons into a single fully-connected layer (i.e pooled classification). For reference, our base authentication consists of only accelerometers and only camera.

Potential Schemes:

- Ensemble Classification

- Feature Concatenation

- Pooled Classification

Spoiler Alert

Because of the failure in the accelerometer classification, only the ensemble classifier was carried out :(. Note that the difference in shape of the accelerometer traces and video made feature concatenation very complicated. In addition, pooled classification will result in incredibly confusing network architectures.

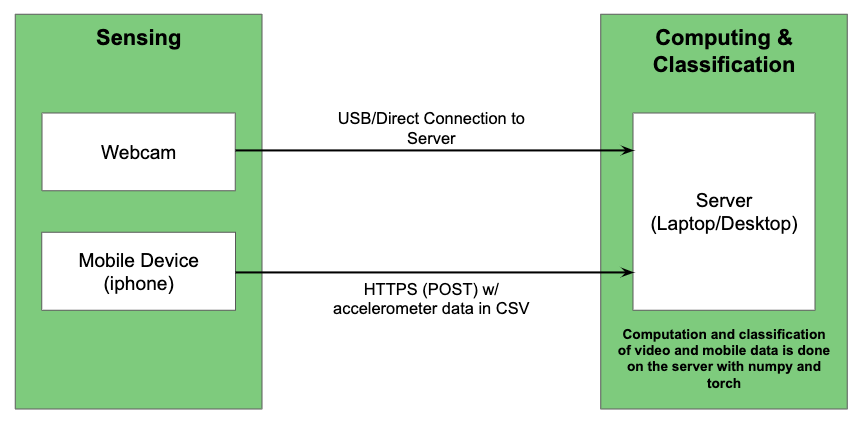

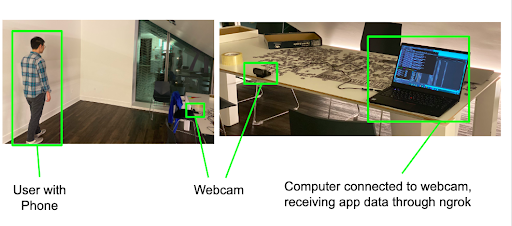

Data-Collecting Setup & Our Dataset

Overall, we collected 60 accelerometer traces and video recordings - 20 for each team member. The data was collected using a web-server running on a laptop. Once the subject presses a button on an app, the mobile device and video camera start recording data. After the subject presses the button again, the recording stops and data is sent to the server.

Implementation Logistics

The server was programmed with Flask using ngrok tunneling to make it accessible over the internet. To start collecting data, we press a button on a custom IOS app that sends a GET request to the web server url url (something like https://{random_string}.ngrok.io/record/{label_name}).

For consistency, we took all of our recording sessions on a well-lit, blank background in a dorm.

Below is a snippet of an accelerometer trace in CSV form.

| accel_x | accel_y | accel_z |

|---|---|---|

| 149 | -621 | -723 |

| 71 | -561 | -796 |

| 19 | -390 | -760 |

| 79 | -410 | -1202 |

| -56 | -362 | -1036 |

| -106 | -403 | -846 |

| -27 | -493 | -786 |

Concession: Offloading Computation

Most of the computing, training, and classification was done in a “server” model (i.e run on a random desktop). It’s not really mobile computing if we offload all our compute in a client-server model. I would consider collecting the information from the phone’s sensors as computing, so close enough.

Offloading compute onto a separate device isn’t unheard of - MAUI researches code offloading for energy preservation, but it’s different. In addition there are ways of supporting trained machine learning models on mobile devices. Apple supports machine learning on the IPhone with CoreML. All of these sophisticated solutions were pretty low priority given the time crunch.

Classification

Gait Recognition through Accelerometers

The classification model based on accelerometer values was named “GaitNet” - a type of convolutional neural network. The network works by treating data traces with T entries for N features as a T x N matrix and convolving over this matrix with a kernel of different sizes. It then maxpools the output of the convolution layers into two fully-connected layers (like a traditional neural network) - the last layer applies the softmax transformation to output a probability distribution of classifications. GaitNet used stochastic gradient descent with a learning rate of 0.001 and a momentum of 0.05.

Performance & Results

The mode accuracy of GaitNet’s trainings was ~34-35% accuracy - which is as good as randomly guessing. This indicates that GaitNet has no strong predictive power (a classifier that always guessed a single result would maintain that same accuracy rate). Interestingly, occasional retraining and testing of GaitNet prediction showed a 70% accuracy rate - indicating that GaitNet could have predicative potential, but these results only occur 10% of the time and were probably just by chance. Changing the pooling parameters, reducing/increasing dropout rates, and other tuning tricks did not lead to a significant increase in performance.

There are several possible factors for the poor performance of GaitNet relating to data-recording configuration such as the length of traces, lack of additional features, or overly simplistic network architecture. One possibility is that the amount of data (length of traces) was insufficient and we lacked feature richness (i.e gyroscopes). Another possibility is that our version of a CNN gait classifier is too simple. For example, the architecture used in [3] uses both a CNN and LSTM to form a pooled feature vector (which then turns into a fully-connected layer with softmax transformation).

Gait Recognition Through Video

The vision based classification uses a pretrained model from this wonderful github repo. The model uses the frames of a video as inputs and outputs an identification vector. More specifically, two networks in the repository (HumanPoseNN and GaitNN) translate this data to human pose descriptors, and uses these poses in sequence (a LSTM) to generate an identification vector. Since the identification vectors seemed well formed and linearly separable, we used an SVM classifier for the identification vectors.

Hyperparameters were tuned using sklearn’s GridSearchCV. The SVC() model fit the model to the identification vectors (derived from the video data) and the labels as tuples. SVC helps find optimal parameters given a grid of parameters. The best regularization parameter (C) was 1, the optimal kernel used to transform data was a gaussian RBG, and the optimal gamma was 0.001.

Performance

This model worked very well! The results are below!

| User ID | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.93 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.91 |

| Acc Type | Results |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.94 |

| Macro Avg | 0.95 |

| Weight Avg | 0.94 |

Conclusion & Results

To summarize, GaitKeep was an attempt to gait authentication with multiple sensors and deep learning. Although there was decent investment into the infrastructure and testing of GaitKeep, timing prevented us from fully evaluating our ideas. As a result, only the vision portion of the authentication system worked well and we weren’t able to conclude if we could augment security with other sensors. The only disappointment I felt was that we never got to evaluate the viability of our main idea.

The main failure of this project was the mobile device classification. When reading about a convolutional approaches to gait recognition through mobile devices, we drastically underestimated the length of data needed and the complexity of the model structure. We did understand that we needed more features (gyroscopes), but bugs prevented us from fitting it in correctly.

In future iterations, I would start with more sensor types and a more complicated network structure to see if that is enough to increase accuracy. The length of video clips were good enough for our video classification, so I’m hesitant to increase the recoding sessions.

Footnotes & Additional Papers

[1] OU-ISIR has an amazing biometrics Database - although you need to request for permission http://www.am.sanken.osaka-u.ac.jp/BiometricDB/

[2] https://github.com/marian-margeta/gait-recognition

[3] Q. Zou, Y. Wang, Q. Wang, Y. Zhao and Q. Li, “Deep Learning-Based Gait Recognition Using Smartphones in the Wild,” in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 15, pp. 3197-3212, 2020, doi: 10.1109/TIFS.2020.2985628.

[4] M. P. Mufandaidza, T. D. Ramotsoela and G. P. Hancke, “Continuous User Authentication in Smartphones Using Gait Analysis,” IECON 2018 - 44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Washington, DC, 2018, pp. 4656-4661, doi: 10.1109/IECON.2018.8591193.

[5] Hong Lu, Jonathan Huang, Tanwistha Saha, and Lama Nachman. 2014. Unobtrusive gait verification for mobile phones. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers (ISWC ’14). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 91–98.

[6] Yuanying Chen, Wei Dong, Yi Gao, Xue Liu, and Tao Gu. 2017. Rapid: A Multimodal and Device-free Approach Using Noise Estimation for Robust Person Identification. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 1, 3, Article 41 (September 2017), 27 pages.

[7] M. P. Mufandaidza, T. D. Ramotsoela and G. P. Hancke, “Continuous User Authentication in Smartphones Using Gait Analysis,” IECON 2018 - 44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Washington, DC, 2018, pp. 4656-4661.

[8] N. Takemura, Y. Makihara, D. Muramatsu, T. Echigo, and Y. Yagi, “ Multi-view large population gait dataset and its performance evaluation for cross-view gait recognition”, IPSJ Trans. on Computer Vision and Applications, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 1-14, Feb. 2018

[9] Hong Lu, Jonathan Huang, Tanwistha Saha, and Lama Nachman. 2014. Unobtrusive gait verification for mobile phones. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers (ISWC ’14). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 91–98. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/2634317.2642868

[10] A. Jain, A. Ross, “An introduction to biometric recognition”, IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 4-20, 2004.

[11] Gafurov, D.: A survey of biometric gait recognition: Approaches, security and challenges. In: NIK conference (2007)

[12] P. J. Phillips, A. Martin, C. L. Wilson and M. Przybocki, “An introduction evaluating biometric systems,” in Computer, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 56-63, Feb. 2000.

[13] Emiliano Miluzzo, Nicholas D. Lane, Kristóf Fodor, Ronald Peterson, Hong Lu, Mirco Musolesi, Shane B. Eisenman, Xiao Zheng, and Andrew T. Campbell. 2008. Sensing meets mobile social networks: the design, implementation and evaluation of the CenceMe application. In Proceedings of the 6th ACM conference on Embedded network sensor systems (SenSys ’08). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 337–350.

[14] S. Eberz, G. Lovisotto, A. Patanè, M. Kwiatkowska, V. Lenders and I. Martinovic, “When Your Fitness Tracker Betrays You: Quantifying the Predictability of Biometric Features Across Contexts,” 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, 2018, pp. 889-905.

[15] Huan Feng, Kassem Fawaz, and Kang G. Shin. 2017. Continuous Authentication for Voice Assistants. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (MobiCom ’17). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 343–355.

[16] Eduardo Cuervo, Aruna Balasubramanian, Dae-ki Cho, Alec Wolman, Stefan Saroiu, Ranveer Chandra, and Paramvir Bahl. 2010. MAUI: making smartphones last longer with code offload. In Proceedings of the 8th international conference on Mobile systems, applications, and services (MobiSys ’10). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 49–62.

[17] Tiffany Yu-Han Chen, Hari Balakrishnan, Lenin Ravindranath, and Paramvir Bahl. 2016. GLIMPSE: Continuous, Real-Time Object Recognition on Mobile Devices. GetMobile: Mobile Comp. and Comm. 20, 1 (July 2016), 26–29.

[18] S. R. Das, R. C. Wilson, M. T. Lazarewicz and L. H. Finkel, “Gait recognition by two-stage principal component analysis,” 7th International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FGR06), Southampton, 2006, pp. 579-584, doi: 10.1109/FGR.2006.56.

[19] Valentin Radu, Catherine Tong, Sourav Bhattacharya, Nicholas D. Lane, Cecilia Mascolo, Mahesh K. Marina, and Fahim Kawsar. 2018. Multimodal Deep Learning for Activity and Context Recognition. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 1, 4, Article 157 (December 2017), 27 pages. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3161174