A (More) Complete Guide To Web Scraping

17 Feb 2020- Introduction

- Understanding Web Scraping

- Building the crawler

- Understanding HTML & URLs

- Advisable Practices

- Common Issues: Dealing with interactivity and Javascript

- Common Issues: Rate Limits

- Common Issues: 2FA

- Advanced Concept & Design: Parallelization

- Rules & Regulations

- Alternatives to Building from Scratch?

- Conclusion & Next Steps

- Footnotes

Introduction

My critique of popular tutorials on web scraping is that they teach you how to scrape for a specific situation. While the tutorial does its job and work for simple cases, these tutorials don’t teach enough about the fundamentals of the web, or troubleshooting techniques to let beginners extend their crawlers. I struggled to find complete solutions for my problems and had to stitch various resources from books, the internet, and my experiments.

As a result, I wanted to take a “more complete” approach in this tutorial. This means this article won’t be so “high-level” where every complication is abstracted (removing the learning process), but also not so “low-level” where the activity is excessively time-consuming and slow. Hopefully, this explanation should let a beginner acquire topics related to scraping, and be able to research and learn for themselves.

NOTE: You don’t need to read the whole piece - this blog post was a lot longer than I intended it to be (in retrospect I should have just broken this up). Just read the parts that apply to you. Also, I always recommend doing additional research!

Understanding Web Scraping

Web scraping is the process of automatically extracting information from the web. Bots and crawlers leverage the structure of websites (HTML & JS) and their addresses (URL) to extract data automatically and consistently.

Why should I scrape from the web?

Situations that require scraping are niche; however, if you need data for:

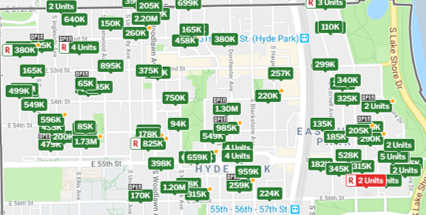

- a novel/cool visualization

- exploration of new ideas involving predictions on user behavior

- an original research project

- a break from existing Kaggle datasets for your sick machine learning skills (although Kaggle has a lot of datasets)

Use Cases of Web Scraping

The data you want exists somewhere (how else would it exist?) - whether it’s on a companies servers, massive tech aggregator, or data vendors. The problem is that the capital or security clearance needed isn’t worth it for a hobby or small experiment.

Limitations of Web scraping

Building a crawler can’t solve all of your data collection needs.

Scrapers/crawlers can be highly specialized and finicky as a result.

- Websites can change their front end that make it difficult to reuse homemade scraping functions

- Websites/services actively implement measures to prevent scraping. Social media sites impose a limit on the number of different profiles you can view in an hour.

When allocating time into a data-project, it’s important to remember these limitations and not allocate too much time or energy into this phase. Creating beautiful, reusable code is always good, but it is not economical depending on your use case. Don’t spend weeks programming something that will only run once (and for a short time).

Building the crawler

Setup

Even though a lot of web scraping tutorials are in Python (cause it’s a lot easier), scraping is language-agnostic. I use python 3.7 with beautifulsoup4 and requests. You don’t need these libraries to scrape! You could replace beautifulsoup4 with regular expressions, and requests with Python’s native HTTP library (or make your own). However, using high-level libraries make web scraping significantly easier (remember where you want to be spending the majority of your time).

Reminder: Building a crawler is an iterative process - testing your requests and extraction methods through trial and error (using an interactive shell) allows you to prototype a crawler much more quickly. For instance, I like testing my crawler’s accuracy by using a jupyter notebook to test an initial strategy and iteratively refining it.

Web Scraping (Abstractly)

Conceptualizing web scraping as a series of lets us ignore certain details and focus on the main ideas. Implementation is important, but the stress of planning for additional details make it hard to start.

- Figure out which URLs (web addresses) to visit

- You could decide by following a pattern of urls (i.e xyz.com/page=1; xyz.com/page=2, etc)

- You could request a page and determine additional pages to visit from there (ex: visiting a profile and adding the user’s friends to a queue)

- Make a request to the URL (and receive the webpage’s content)

- Make a HTTPS request in your language of choice

- Save the webpage’s source (underlying HTML)

- Parse the web page’s HTML to extract desired information

- Save the structured data

Psuedocode template

With some minor tweaks this could should work for simple sites. [insert joke about how Python is pseudocode har har har]

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import os

def download_urls(urls: list):

for index, link in enumerate(urls):

r = requests.get(link)

if(r.status_code == 200):

with open('saved{}.html'.format(index), 'wb') as file:

file.write(r.content)

return

def store_data(data):

'''

Store Data

'''

def scrape_saved_html(data_dir):

for fname in os.listdir(data_dir):

with open(fname, 'rb') as file:

soup = BeautifulSoup(file.read(), 'html.parser')

'''

Extract Information

'''

store_data(extracted_info)

return

if __name__ == '__main__':

pages = ['www.xyz.com/page={}'.format(i) for i in range(10)]

download_urls(pages)

scrape_saved_html('/')

print('done scraping')

Understanding HTML & URLs

Now that we know the abstract steps to web scraping, the next step is to figure out implementation - the how to scrape and which pages to scrape. Having an “okay” understanding of the web will make requesting and parsing (steps 1 and 4) much easier.

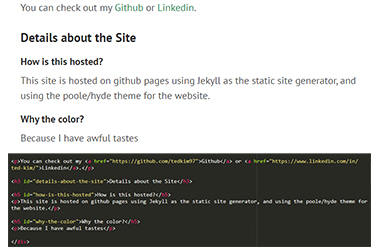

On a high level, HTML represents the content of the page while a URL indicates it’s location. A website will have well-structured pages (HTML) and locations (pages). Using our understanding of HTML, we can exploit the structure of websites (HTML DOM) to make parsing our desired data simple and predictable (the how), and our understanding of URLs to know which pages to go to (the which).

HTML?

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is the standard markup language for information on the web. HTML (along with CSS, JS, and more) is responsible for building all the pretty websites on the web. Websites have an underlying source that instructs your browser to display content properly. Building the contents of this site (like items on a store page) to be dynamic involves creating well-structured HTML (i.e don’t randomly create elements and tags to store product information). Assuming the site maintains this structure, a crawler can exploit that to extract data on a larger scale. Not all websites are identical, and the more fluent we are with web dev the faster we can build the crawler.

HTML Tags & Elements

The HTML (or HTML DOM) is featured around “elements”, which are treated as objects. Look at any HTML file and you’ll see tags like <div>, <p>, , etc. Furthermore, HTML & CSS allows us to create classed elements with custom styling defined in a `.css` file. These tags are structured in a tree structure - where the tag actually hints at whats inside. Finding these elements can be done by ID, tag name, class name, CSS selectors, and HTML object collections[^1].

Iterating (Quick and Dirty)

The approach I take is view the downloaded HTML in a browser or sublime. I find an example data point (like “ABC Mason Jar”) I want to find and “CTRL + F” through the file for a match. The desired data should have some element or tag that indicates that its usage (like <div class="productname">). Assuming the web developers were consistent, the pattern you picked should repeat on different pages.

Then we can use beautifulsoup4 to find elements fitting that like “<div class=productname>”. You don’t need to be super precise here, in the worst-case scenario you can collect excess information, and find clever ways of excluding that information

URL?

URL (Uniform Resource Locator) is a reference to a web resource that specifies its location and a mechanism for retrieving it. Even though they might not be intelligible to us (ex amazon.com/soap/dp/B07M63H81H?pf_rd_r=7NDCD524VXDHCMBVQGS9&pf_rd_p=8f819d9f-3f10-459c-877d-64ffa525d3b4&pd_rd_r=b5353e1b-cc55-40e2-8050-4105565358f1&pd_rd_w=LaiQz&pd_rd_wg=NCNvQ&ref_=pd_gw_bia_d0), they are not random.

Understanding the structure of URLs is important because websites/web services (should) have well-structured URLs. With some clever experimenting, we can puzzle together the structure of URLs of a site.

Iterating (Quick And Dirty)

The approach I take for finding URLs schemes is to type in modified URLs into my browser. An example I like to use for how to play with URLs is to go to ultimate-guitar.com and click on “tabs”. Then I experiment with how different search settings changed the URL in my address bar.

Below are some URLs I cobbled together by puzzling the structure. It seems that this site has a relatively simple URL scheme! We use & to join query filters (page=3, type[]=guitar), and we notice that the ordering of the filters doesn’t matter. In addition, the ? indicates that we’re sending a query to the server.

ultimate-guitar.com/explore?

ultimate-guitar.com/explore?page=3

ultimate-guitar.com/explore?type[]=Ukelele%20Chords

ultimate-guitar.com/explore?type[]=Ukelele%20Chords&page=4

ultimate-guitar.com/explore?type[]=page=4&Ukelele%20Chords

ultimate-guitar.com/explore?type[]=page=4&Guitar%20Chords

For a deeper understanding of getting/sending URLS, one should research “REST” (Representational State Transfer) for the web.

Advisable Practices

I hesitate to say “best” (which is why I don’t) because I am not an authority on scraping/crawling. However, I think that some of these practices below should be followed.

Save HTML

When you’re scraping, store a copy of the page (the HTML) onto a storage device (an external drive, the drive your OS is on, a network attached storage, etc).

You might observe that saving HTML pages to your disk is unnecessary! A crawler could just request pages, keep them in memory, and extract data, and free the memory after extracting. However, in the process of testing and debugging a crawler, someone might execute different variations of the code to fix any problems they have.

If you do this without a local copy of the webpages, the crawler will make a lot of repeat requests to the host as a result - which is an unnecessary cost to the host, waste of your bandwidth, and may result in an IP ban. In addition, storing the source pages will allow you to look for mistakes and validate the correctness of your data. In summary, optimizing write endurance on drives is not worth it.

Anonymize/Pseudonymize Data

There are two approaches to sanitizing data: anonymization and pseudonymization. Anonymization prevents re-identification of a data point that can’t be used to identify anyone while Pseudonymization allows the data point to be recovered given additional information.

You should anonymize data to protect people’s privacy, and make sure your anonymization scheme does its job effectively. An example of a bad anonymization scheme is a lookup table (ex: john doe => 1, jane doe => 2). If you Anonymize data with this lookup table, you can recover the person’s ID by reversing the lookup - protecting no one’s data.

Anonymization: Deleting the ID: Just deleting the ID of the data point is the best way of maintaining anonymity. However, if you need to be able to identify behaviors over time or execute ‘joins’ across different datasets deleting ID only hurts your work. If you need an alternative, the solution below may help you out.

Anonymization/Pseudonymization: Salted Cryptographic Hashes:

Disclaimer: this isn’t a perfect solution! There are plenty of articles that point out the problems with this approach - mainly that it can’t truly anonymize data. However, this solution works pretty well for a pseudonymization scheme.

Cryptographic hashing is a method of taking an input of any length and outputting a (seemingly)random fixed-size hash. The reason why they’re important is that cryptographic hash functions have a set of properties that make it ideal for certain security applications. Fun fact, cryptographic hashing and salting are common practice in storing passwords. This is why a company can’t tell you what your password is when you forget - the company doesn’t know it themselves, just the salted hash of your password.

We will ignore the engineering of cryptographic hash functions and look at their properties, and why they might be helpful for our use case.

A good cryptographic hash function should be:

- Deterministic : Hashing some value with the hash function will always be the same w.r.t the value. (

SHA256('abc') == SHA256('abc')) - (Practically) Collision Free/High Collision Resistant : (Good) cryptographic hash functions are collision resistant, meaning you won’t find two inputs that result in the same outputted hash (or a “collision”). In reality, collisions are possible (making them not truly injective), but very unlikely. Refer to this stack exchange post if you want an idea of how unlikely.

- One-way (No inverse) : This means that it should be difficult to find the inverse of

hash(x)besides brute-forcing all X’s. Assuming you’re using a popular hashing method, this should be given. If you could quickly invert SHA-256 you would be the most powerful person alive. This property is also called Pre-image resistance. - Avalanche Effect : A change in a bit of the original input should drastically change the resulting hash - preventing any correlation between hashes of similar inputs.

- Easy to compute : this system wouldn’t be very usable if it were slow to compute

With these properties, we have a potential anonymizing scheme that allows for consistent identification when hashing an ID (determinism), you cannot have faulty duplicate ID’s (collision resistance), you cannot find the ID given a hash (one-way), you cannot try to solve for patterns through hashes (Avalanche effect), and it’s fast (easy to compute). However, naked hash functions alone are not good enough.

In fact, there exists an easy attack to naked hashes. Since usernames are meant to be public - an attacker could run a couple of hashing algorithms on those publicly available usernames, and sees if any of the generated hashes match your dataset. This is basically an easier version of a popular encrypted password attack (the rainbow table attack)!

As a result, a popular technique to circumvent this is to “salt” the input - which is the processing of appending information to the input, to completely change the output. An example would be hash(x||blargh) != hash(x). Now as long the attacker doesn’t know your salting patterns, they won’t be able to find IDs as easily.

Despite all this effort, you can’t truly anonymize data as long as the salting technique and CHF are known (we can recover user IDs if we have a list of usernames and the salt+hash scheme). This paper “Introduction To The Hash Function as a Personal Data Pseudonymisation Technique” lists some strengths and weaknesses of using hashing as a pseudonymization scheme1.

Implementing cryptographic hash functions is complicated, so I recommend using a library (like pycryptodome).

Be Good!

Don’t scrape for bad purposes! If you’re trying to use web scraping to detect botting or astroturfing, I encourage you to do that! However, don’t do it to bad things like sell people’s information or undermine democracy.

Common Issues: Dealing with interactivity and Javascript

One common issue people face is dealing with use interactivity/extracting information from pages with javascript. Modern websites don’t load information at once. Instead, they’ll display information with a button press (“load more!”, “expand!”).

Another situation is that a website may involve some sort of login (although if they have a login, scraping is probably against TOS). The reason why this is a problem is that our naive crawler can’t just make a POST request with login credentials or press a button. and expect to get back login access (it’s a whole process with tokens, authorizations, etc).

A fix to this problem is to use selenium2 - a tool for automating browser tasks - to control a browser session and scrape through the human computer interface. People primarily use Selenium for automating web testing, but we can use it to run a crawler.

Selenium: Locating Elements

Below is a simple example where you locate a “load more” button by identifying the button’s class name and “clicking” it through selenium.

from selenium import webdriver

button_class = 'masonry-load-more-button'

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=browser_options)

driver.get('somewebsite.com/test')

try:

load_button = driver.find_element_by_class_name(button_class)

load_button.click()

time.sleep(2) # give time for the content to load

web_content = driver.page_source

'''

save web_content

'''

except:

'''

NOTE: the webdriver might fail to find the button for several reasons.

Common reasons include:

1) typo in the class name

2) the Internet did not load the button in time

3) the button does not exist on the page (ever)

'''

print("failed to find button")

Selenium offers a way of retrieving the first example that fits the criteria (find_element_by_class_name), or every element that fits the criteria (find_elements_by_class_name). It’s up to you to decide how to locate the right elements to interact with, and how to ignore the wrong buttons.

Keep in mind there is more than one way of identifying elements in Selenium - you can also locate them by id, name, xpath, link_text, partial_link_text, tag_name, and css_selector. I recommend you read the documentation for proper usage and details.

REMEMBER: Make sure you save the page source after you’ve interacted with the page and all information has been loaded.

Selenium Tip: Handling Exceptions

Selenium throws exceptions for situations where it can’t execute an instruction. If you don’t want to reset your crawler every time you run into the exceptions, you should run some try/catch clauses in your crawler. If you want to handle specific exceptions, you need to import them from selenium like:

from selenium.common.exceptions import NoSuchElementException

try:

button_press(x)

except NoSuchElementException:

print("could not clickbutton")

'''

However you handle it

'''

except:

print("Different exception")

'''

Do whatever you want

'''

Selenium Tip: Manage Browser Version

If you try to open a webdriver, and get an error like ...: Message: session not created: This version of ChromeDriver only supports Chrome version XYZ. The solution is to install a compatible webdriver from the internet. There is another solution that requires no additional configuration detailed in this stack exchange post if you don’t want to manage something like that.

Selenium Tip: Headless Mode

You’ll notice that when you run the the crawler through selenium, a browser session will pop up on the screen. If you don’t want this, you can hide the screen (but keep the activity) by adding a "--headless" option to your webdriver settings. Below is an example of how to use this feature in python.

from selenium import webdriver

browser_options = webdriver.ChromeOptions()

browser_options.add_argument('--incognito')

browser_options.add_argument("--headless");

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=browser_options)

driver.get(url)

Selenium Tip: Detaching

I’m not sure if this works anymore, but you can detach your browser so that when it completes, the browser session stays intact. This is helpful for visually debugging.

browser_options = webdriver.ChromeOptions()

browser_options.add_experimental_option("detach", True)

Selenium Tip: Implicit Waits/Waiting

Selenium offers Implicit Waits - which is a way of pausing the web driver until a certain element exists (like when a button is done loading, or if a certain tag appears). This can create a more robust scraper that’s less likely to miss information. However, I personally have never gotten Implicit Waits to work. I’ve looked at documentation and examples on the internet, but I have never gotten Implicit Waits to work for me. I could be misunderstanding how ImplicitWaits worked, coding it incorrectly, or it’s an issue with the Selenium Python binding (not likely), but I have never gotten it to work.

I could have spent 1-2 more hours trying to solve the problem, but I just judged that it was faster to time.sleep(5) the driver, and move on. This approach has drawbacks. I could be wasting a lot of time waiting even though the contents of the page has loaded. In addition, the driver might not be waiting long enough (which destroys the point of the implicit waits), but in my experiences time.sleep has been an adequate solution.

from selenium import webdriver

import time

browser_options = webdriver.ChromeOptions()

browser_options.add_argument('--incognito')

browser_options.add_argument("--headless");

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=browser_options)

driver.get(url)

time.sleep(5)

'''

Scrape Content

'''

Common Issues: Rate Limits

Websites will put in rate limits on the number of page visits per hour (ex: you can only request 100 twitter handles per hour), and you will never be able to beat this limit. This limit is placed to prevent people from tracking social media information, and it’s very effective.

As of now (according to Statista) there are around 1.7 billion daily active facebook users. If we are limited to 100 profile requests per hour, even if we visit 1% of the DAU, then it would take 170,000 hours, or 7,083.3 days to requests those users… Adding machines can speed this up, but each additional machine will only bring a marginally smaller reduction in time3.

Common Issues: 2FA

2FA poses a problem because there is no (easy) programmable way of reaching your texts. There are some workarounds, but no perfect solution. Free services (google voice, skype) do not work. Companies with 2FA will recognize these are not real phone numbers and won’t allow you t register.

Cellular Modules

We can use a USB cellphone module to connect a SIM card to your computer. Here are some links to products that can help you do this:

- Adafruit product 1 - programmed through Arduino and can interface with PySerial. The downside being that it requires a LIPO battery to power the cellular module (in addition to the power the Arduino gets from USB).

- Adafruit product 2 - see above

- Huawei e8372 - a 4G LTE dongle that is powered solely through USB. There is a wonderful python library that interfaces with this device for you! One of the contributors describes it in his blog

PRO: Customizable, Robust CON: Very expensive (cost of dongles, arduino, and a new SIM with phone plan)

Text Forwarding Services (Android only)

If you have an android phone, there are apps that can read texts and forward them to your email. I would not recommended this if you care about security. If you’re desperate, you could program your own android app that does the same thing.

PRO: Cheap and easy if you already have an android phone CON: Incredibly sketchy and inconsistent

Advanced Concept & Design: Parallelization

Web scraping can benefit significantly from parallelizing the task. Having multiple scraping processes run at once is a straightforward extension. We can use Python’s thread library to easily implement it. Each scraping process is independent of each other, so you won’t have to worry about shared data-structures and such.

Downloading:

import threading

num_threads = 10

URLS = ['xyz.com/page1', 'xyz.com/page2', 'xyz.com/page3', ...]

index_slice = len(URLS) / num_threads

def download_html(datadir, urls):

for link in urls:

'''

Request Page

'''

saveto(datadir, data)

return

for i in range(num_threads):

thread_arg = ('mydata/', URLS[(i * index_slice): (i+1) * index_slice])

tmpt = threading.Thread(target=download_html, args=thread_arg)

tmpt.start()

Extracting:

import threading

import os

num_threads = 10

PAGES = ['mydata/{}'.format(fname) for fname in os.listdir('mydata/')]

index_slice = len(PAGES) / num_threads

def scrape_data(webpages: list, additional_params):

for src in webpages:

'''

Scrape

'''

writeto(database, scraped_data)

return

for i in range(num_threads):

thread_arg = (PAGES[(i * index_slice): (i+1) * index_slice], 'abc', 6)

tmpt = threading.Thread(target=scrape_data, args=thread_arg)

tmpt.start()

Complications

These complications will never occur unless you’re working on a massive scale. I wrote these down just so people are aware of the limitations. Hardware cannot be abstracted, and those limitations prevent us from speeding up scraping INFINITELY.

Reading from File

When you’re reading from a Hard Disk Drive, you could (potentially) be limited by how fast the disk spins on your HDD! Similar story for an SSD that interfaces through SATA or PCIe (granted it’s probably much smaller of a bottleneck). Granted I have not done much more additional research into this.

Network Bandwidth

In addition, network bandwidth can be a limitation. If you don’t have enough network bandwidth, downloading a bunch of files at once may be the same thing as downloading them in sequence.

Writing to files

Writing to a single file with a multi-threaded approach is more involved (multiple threads cannot just write to a single file arbitrarily - this could result in fatal errors). What you could do is use a python binding to a database application that abstracts multi-threaded writes (like pymongo).

Rules & Regulations

Robots.txt

Websites normally have a robots.txt file that indicates who can interact with the website and how. An example would be amazon.com/robots.txt or google.com/robots.txt. You’ll see that in allows and disallows crawlers access to certain locations within the site.

Legal Complications

The rules and regulations in web scraping are complicated - there exists lawsuits and rulings about web scraping. As of 2020, courts ruled that scraping was “okay”, but this rulings is in the process of being appealed. I recommend googling whether web scraping is punishable by death.

On another note, I will say that I have never read articles of a college student being jailed for scraping a website.

Alternatives to Building from Scratch?

There are plenty of services/platforms that can abstract a lot of the work in web scraping. I don’t have any personal experiences with them, but I feel like I should let readers know they exist. Octoparse and Scrapy are some that I’ve heard about.

Conclusion & Next Steps

In conclusion, I hope this article gave you a more complete understanding of how to build a scraper, and retool it for your specific needs. In addition, you’ll have a reference for more advanced topics that can increase the flexibility/speed of your crawler to fit your needs.

If you’re new to data projects, this is not going to be the hardest part of your data project. This is only the first step (sourcing). You’ll still need to clean, preprocess/reorganize, explore, and document it. Good luck!

Footnotes

-

https://edps.europa.eu/sites/edp/files/publication/19-10-30_aepd-edps_paper_hash_final_en.pdf ↩

-

Even though working with the Selenium Python API can be a bit clunky (long class names, importing a lot of different subpackages), the minor, unergonomic aspects are worth the flexibility. ↩

-

In case you need a math demo: We can model a function that tells us the total time to finish scraping like: \(f(n) = \frac{T}{n}\) where \(n\) is our number of crawlers. Our derivative with respect to \(n\) is \(f'(n) = -\frac{T}{n^2}\). This means that an increase in \(n\) results in a decrease of \(f'(n)\) - meaning that the rate of growth for \(f(n)\) is slowly decreasing. ↩